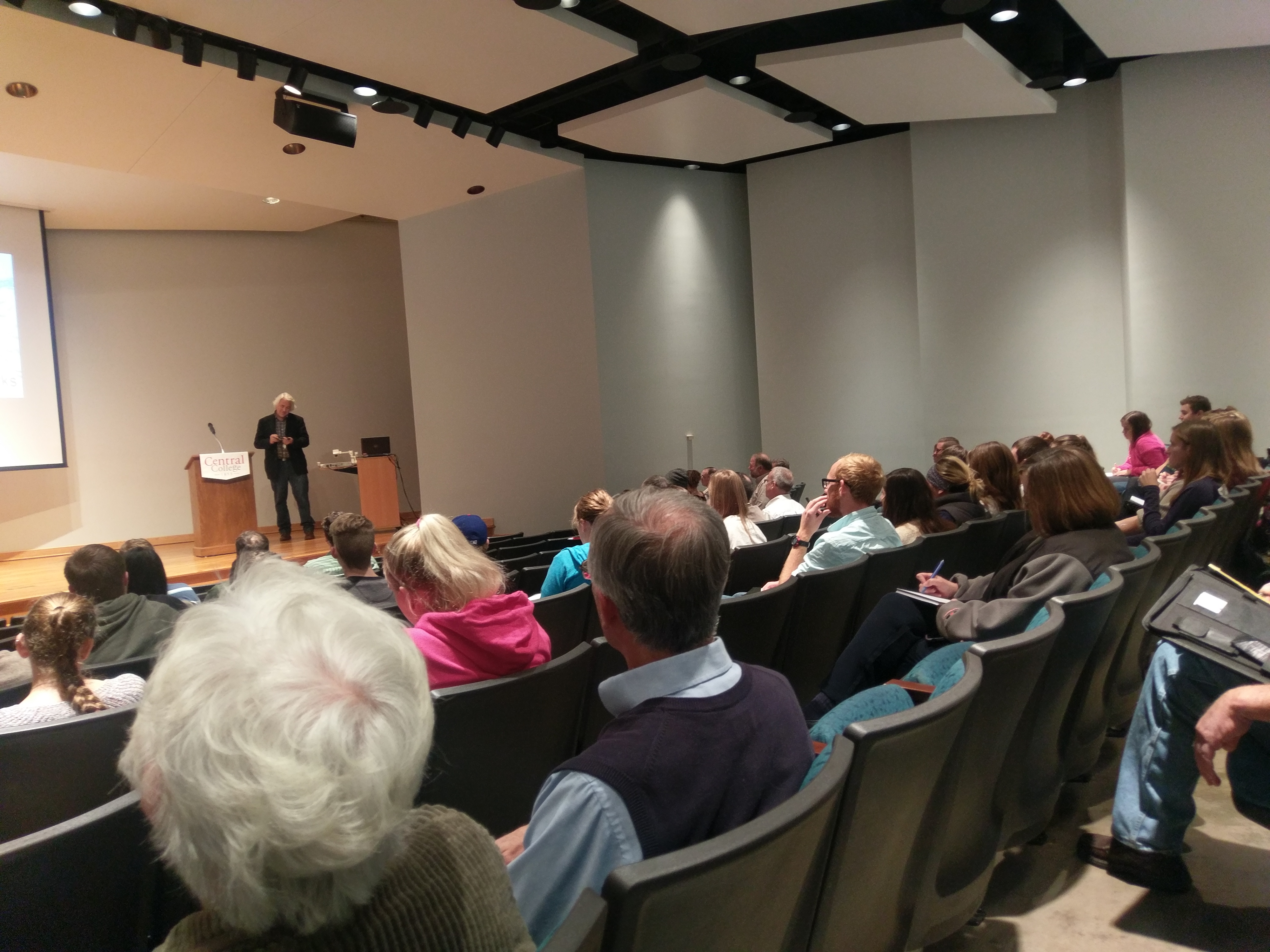

Des Moines Water Works CEO Bill Stowe discussed water quality issues at Central College earlier today.

He spoke to a crowd of approximately 70 people, including farmers, professors, high school and college students.

Stowe is spearheading a lawsuit from Des Moines Water Works against three rural counties northwest of the state’s capital for what he tells KNIA/KRLS News is aimed at holding those responsible for high nitrate concentrations. Stowe says industrial agriculture is the primary source of nutrients in surface water they treat for 500,000 people.

“The background of the lawsuit really involves decades of discussion with industrial agriculture, attempts at collaboration, but then a realization a few years ago, that a lot of talk but no action and results in terms of environmental protection, and that led us to file a lawsuit against Boards of Supervisors in three upstream counties along the Raccoon River and the drainage districts that they manage,” Stowe says.

“Ultimately, our objective is to better protect the source waters, the surface waters of Iowa.”

Stowe says Des Moines Water Works spent $1.5 million in 2015 to remove the nutrients from surface water they pull from the Des Moines and Raccoon Rivers.

“We see a significant degradation, not only in terms of nitrogen and the impacts of from that like nitrate concentrations, which has been something we’ve been fighting for 25 years,’ Stowe says. “We have the world’s largest nitrate removal facility, but we’re seeing other issues begin to emerge.”

Blue green algae as a result of over fertilization is also a problem, he believes, as is the negative impact poorer water could have on economic development. Stowe feels efforts such as the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy implemented by the Iowa DNR, Iowa Department of Agriculture, and Iowa State University, are coming up short in solving the issue of reducing harmful elements in surface water.

“Continued discussions and a voluntary program like the nutrient reduction strategy frankly have failed and our political leadership in this state — Republican and Democratic, have failed to recognize the public health consequences for the trend line we are on and the need to take immediate action.”

When asked about farmers who are struggling financially and may have difficulty implementing better practices highlighted in the nutrient reduction strategy, Stowe feels those with industrial-sized operations are feeling the effects of implementing poor drainage strategies and an overconcentration of resources.

“Most of those businesses receive significant subsidies from the federal government,” he says. “We believe the receipt of those should be tied to conservation practices–they’re not, and so the idea that they are on difficult economic times, I’m sorry, is a reality of a business choice that they’ve made.”

Stowe was invited to speak by Central student Kate Gatzke, who helped organize water week on campus.

“I think that water quality really is something that isn’t necessary in the public eye as much recycling or maybe even gardening as we see here on Central’s campus,” Gatzke, a political science and communications student, told KNIA/KRLS. “I think the use of water just kind of falls by the wayside and I think it’s something people really don’t think about.”

“We’ve heard of Flint, Michigan, we know of a lot of water quality issues that are very severe in places like Africa or Honduras, but we also have water quality issues here that might be a little more invisible.”

Hear more from Stowe on tomorrow’s Let’s Talk Pella.